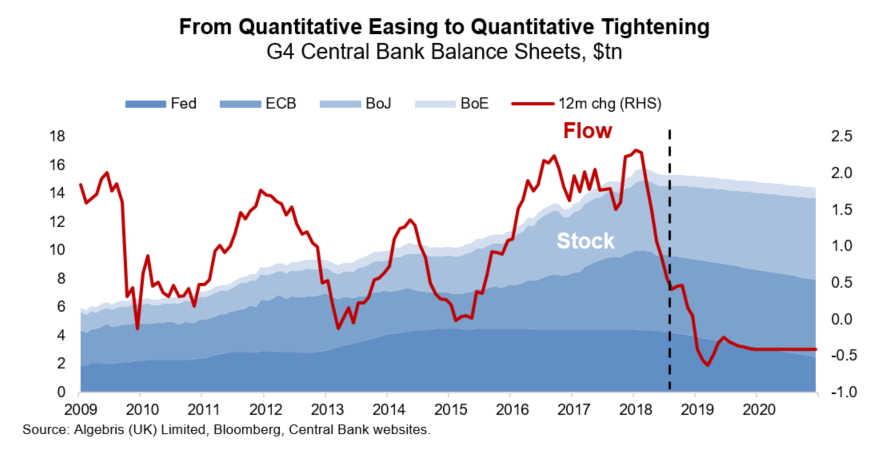

Ten years after the crisis, the quantitative easing music is fading. As the lights turn on, a scary reality is emerging for investors still dancing to the tune of monetary policy: the imbalances which caused the crisis are still present, there is less room for policy error, and a crowd of disenfranchised electorates is asking for payback time.

The bad news is that with a few exceptions, the debt imbalances at the root of the financial crisis have grown larger. Emerging market sovereign and corporate debt has grown thanks to inexpensive liquidity. Even though Eurozone banks have recapitalised, periphery sovereigns remain at record high debt levels, with the exception of Greece. UK households have borrowed up to £200bn of consumer debt. Even countries which were previously considered safe like Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Sweden have developed housing bubbles.

Growing debt and rising fragility in financial markets has also reduced central bankers’ ability to exit stimulus. The Federal Reserve is on its way to normalise policy, thanks to the strength of the US fiscal expansion. However the ECB, the Bank of England, RBA and Bank of Canada may not have the chance to fully normalise rates and build a buffer for intervention before another economic slowdown.

Most importantly, while monetary policy gave a boost to growth, it generated an asset- rich and wage-poor recovery. The resulting wealth inequality and polarisation in opportunities between the young and the old and between large cities vs suburban peripheries has caused the implosion of centrist parties and provided fertile ground for extremists.

Today, investors navigate a world with similar debt overhangs and less monetary policy ammunition than pre-crisis, but with new governments promising to solve their electorates’ problems with unorthodox, simple economic shortcuts.

The Populist Playbook: Dreams, Enemies, False Promises

What do Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Nicolás Maduro, Recep Tayyip Erdo?an, Matteo Salvini and Vladimir Putin have in common?

History is rich of populist examples. Thucydides writes of Cleon, a general who in 427 BC pitted his Athenian countrymen to start a war against Sparta and to decimate the entire population of Mytilene. Like Cleon, populist leaders share at least three common characteristics:

First, they promote themselves as advocates of the people against the elites, promising to bring change and solve their country’s complex economic issues, often with a simple solution. The dream of bringing back America’s florid industrial past, or achieving a cost-free Brexit, or giving citizenship income to Italians regardless of public debt levels are just that – economic dreams.

Second, populists ignite anger against a common enemy: Mexico, the EU, immigrants are some of the recent choices.

Third, once electorates have fallen in their trap, the populist playbook is to perpetuate their dream, at all costs. This includes presenting an alternative reality as well as pursuing unsustainable economic policies. In Italy, an article by the Five Star party recently called the increase in BTP yields a positive, as sales from “foreign speculators” offer more returns to domestic savers. Turkey’s President Erdogan recently urged his countrymen to convert all their savings in Turkish Lira, defending their country against foreign speculators. In most populist regimes, members of the media and other fact-based organisations have often been single out and regarded as enemies of the people.

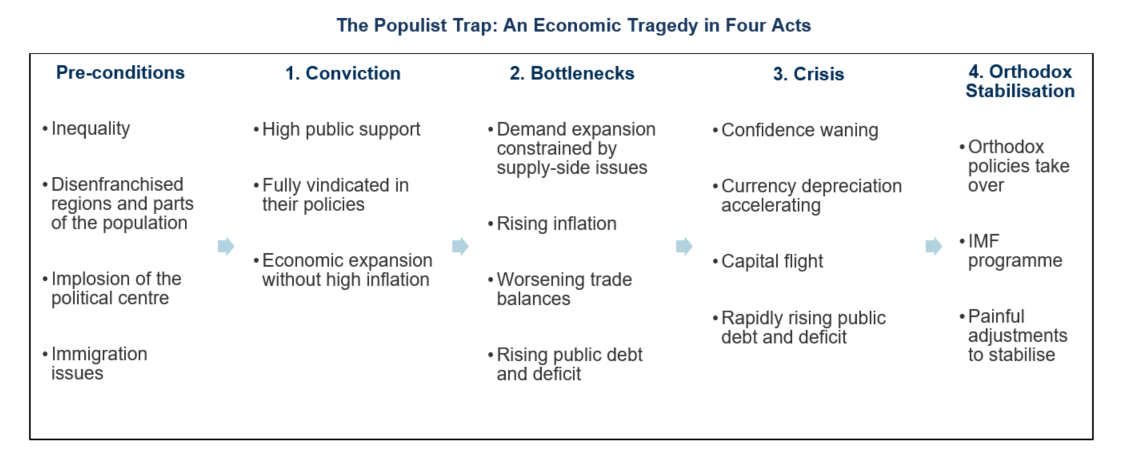

The Populist Trap: An Economic Tragedy in Four Acts

There are typically four phases, for the economics of countries under populist rule, as Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards summarised in the 90’s:

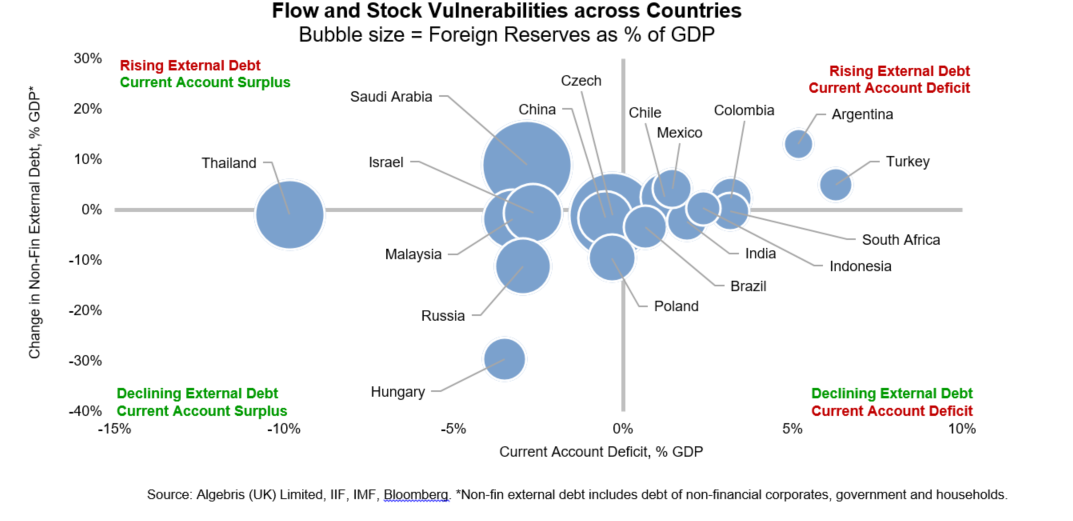

Phase 1: Conviction (Italy, Britain, United States, Brazil). This is the start of a populist policy cycle where the government commands public support and is fully convinced of its proposed solutions for the country’s economic issues. In some cases, the economy may receive a short-term boost from stimulus, while longer term problems are yet to emerge. Italy likely falls in this phase at the moment, while Brazil is at risk going into the October election.

Phase 2: Bottlenecks (Russia, South Africa). In the second phase, a rapid demand expansion driven by stimulus could start to meet supply-side constraints, leading to rising inflation and worsening trade balances. Public debt and deficit also start to grow.

Phase 3: Crisis (Turkey, Argentina, Venezuela). This is when all the economic imbalances in the country manifest and confidence starts to wane. Currency depreciation starts to accelerate, leading to capital flight. Budget deficit and debt climbs rapidly, rendering government policies unsustainable. The central bank gets stuck in a dilemma between hiking to defend the currency and easing to support growth.

Phase 4: Orthodox stabilisation (Greece). This is when orthodox policies take over, often under a new government and with an IMF programme. Structural reforms and austerity measure will be enacted, and the economy will undergo painful adjustments to stabilise.

We can divide populist measures in three categories: the good ones, the ugly ones, which are only good in the short term, and the bad ones.

The Good: Education, productivity, investment. The long-term solutions are to invest and improve productivity: over time, gains in efficiency and productivity are ultimately the key to higher wages and living standards. For too long, government policies allowing to borrow for a new house (or a holiday, or a car), like `Britain’s- Help-to-Buy scheme, have been a cheap substitute for long-term investment in productivity.

The Bad: Trade wars, protectionism, military conflict: trade has been a win-win since the start of economics. Globalisation has helped to reduce poverty, increase healthcare and promote development across the world. However, some have missed out: the middle and low- income classes in developed countries suffered, as production was outsourced elsewhere.

Despite political promises, however, it is difficult to imagine a return to mass domestic industrial production in the U.S. or the UK. Why? The cost of hiring workers in developed markets, where productivity has stagnated over the past decades remains higher than their Chinese or Korean colleagues, who are paid a fraction. A quick, tempting solution is to impose trade tariffs, trying to isolate each economy. In a first round of tariffs, the country imposing them may gain, boosting domestic production for goods that would be otherwise imported. Over time however, this means less imports or a higher cost of goods, which will eventually hurt the workers themselves, as consumers. The UK is a case in point, importing around half of all the goods it consumes. The dream of a clean Brexit with a stronger economy is therefore the economic equivalent of Peter Pan’s Neverland.

In the worst scenario, populism can even lead to military conflict and a humanitarian crisis. Venezuela is a case in point: hyperinflation, rising crime and chronic food shortages have not stopped Nicolás Maduros authoritarian regime.

The Ugly: Universal Basic Income, Tax Redistribution. The last set of policies are the ones that would put a patch on the inequality issue, without addressing its root causes. Redistributing some wealth from the rich to the poor will help to rebalance some of the windfall from QE. However, among the root causes of inequality are a lack of equal access to good education, as well as tax systems which encourage wealth-preservation. Again, the U.K. is a case in point, where non-domiciled wealthy individuals or corporates pay little on foreign assets, while middle-class employed workers are taxed on capital gains as income.

Cleon was killed by Spartans troops as he fled from Amphipolis. While frustrated electorates may be lured to believe in unrealisable economic promises, price action already shows that investors have already much harder to fool. With liquidity from global QE drying up, today’s populists do not fight on the field of battle, but in financial markets. It may be the same investors they blame who will bring them back to reason, or ultimately show them the door.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Algebris e i suoi prodotti o per farsi inserire nella lista di distribuzuione, si prega di contattare il dipartimento Investor Relations all’indirizzo algebrisIR@algebris.com. Gli articoli passati sono disponibilii sul sito Algebris Insights

Questo documento è emesso da Algebris (UK) Limited. Le informazioni contenute nel presente documento non possono essere riprodotte, distribuite o pubblicate da alcun destinatario per qualsiasi scopo senza il preventivo consenso scritto di Algebris (UK) Limited.

Algebris (UK) Limited è autorizzata e regolamentata nel Regno Unito dalla Financial Conduct Authority. Le informazioni e le opinioni contenute nel presente documento hanno solo scopo informativo, non hanno la pretesa di essere complete o complete e non costituiscono una consulenza in materia di investimenti. In nessun caso qualsiasi parte del presente documento deve essere interpretata come un’offerta o una sollecitazione di qualsiasi offerta di qualsiasi fondo gestito da Algebris (UK) Limited. Qualsiasi investimento nei prodotti cui si fa riferimento nel presente documento deve essere effettuato esclusivamente sulla base del relativo Prospetto informativo. Queste informazioni non costituiscono una Ricerca di Investimento, né una Raccomandazione di Ricerca. Con il presente documento Algebris (UK) Limited non organizza o accetta di organizzare alcuna transazione in qualsiasi tipo di investimento, né intraprende alcuna attività che richieda l’autorizzazione ai sensi del Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

Non si può fare affidamento, per nessun motivo, sulle informazioni e sulle opinioni contenute nel presente documento, né sulla loro accuratezza o completezza. Nessuna dichiarazione, garanzia o impegno, esplicito o implicito, viene data in merito all’accuratezza o alla completezza delle informazioni o delle opinioni contenute in questo documento da parte di Algebris (UK) Limited , dei suoi direttori, dipendenti o affiliati e nessuna responsabilità viene accettata da tali persone per l’accuratezza o la completezza di tali informazioni o opinioni.

La distribuzione di questo documento può essere limitata in alcune giurisdizioni. Le informazioni di cui sopra sono solo a titolo di guida generale ed è responsabilità di ogni persona o persone in possesso di questo documento informarsi e osservare tutte le leggi e i regolamenti applicabili di qualsiasi giurisdizione pertinente. Il presente documento è destinato esclusivamente alla circolazione privata per gli investitori professionali.

© Algebris (UK) Limited. Tutti i diritti riservati. 4° Piano, 1 St James’s Market, SW1Y 4AH.