ECB President Draghi asked this rhetorical question at the ECB’s latest press conference, when explaining why monetary policy isn’t close to normalisation. His response, to his own question, was that the world itself is far from normal: the financial crisis ten years ago, the sovereign crisis in 2011 and today, the rising threat of protectionism all call for continued non-conventional monetary measures.

After a brief attempt to normalise policy over the past couple of years, central bankers around the world are going back to easing. Against the rising perils endangering the global economy, Mr. Draghi and Mr. Powell are positioning themselves as white knights, helping to prevent the worst.

A return to monetary easing has been enough to dispel recession fears, which overshot at the end of last year, as we anticipated in December 2018 (The Silver Bullet | 2019: Populism and Volatility, but no Recession). But the question is – will it work this time around?

1. Will more monetary easing work?

At the onset of the ECB’s Quantitative Easing (QE) in 2015, our estimates showed that not only would QE not work in the Eurozone, due to a number of broken transmission channels, but that it would continue for a very long time.

Today, QE infinity, an expression which we coined at the time, is about to become a reality. The Fed is likely to start a mini-cycle of insurance cuts at the end of July, even though financial conditions in the U.S. remain generally loose. The ECB is likely to boost the existing limits of its QE programme, raising the ownership ceiling for bond issues to 50% from the existing 33%, and may cut the deposit rate even further into negative territory.

Financial markets have taken this news with skepticism. On the one hand, rates-related trades have outperformed in H1, not just duration but also bond proxies like utilities in the equity market. On the other hand, however, cyclical assets have underperformed: small caps are lagging large caps, high yield single-B and lower rated bonds have lagged triple-Bs and double Bs, and so on. Put differently, investors are buying the return of loose policy, but they aren’t buying assets linked to growth or inflation. Markets are pricing that there will be more QE, but that it won’t work.

This is consistent with our long-standing concerns on the use of non-conventional monetary policy. Especially in the Eurozone, where banking systems remain fragmented and inefficient and fiscal stimulus is still tepid, QE is unlikely to boost inflation, in our view. Absent a change in fiscal policy, we believe that QE may only prevent the worst case scenario, but its marginal impact on growth will be limited.

2.Are central banks losing independence?

To some extent, easy monetary policy has too long been a substitute for reforms and productivity-boosting investment, as former RBI Governor Rajan has argued. But using monetary policy as a one-size-fits-all patch solution to fix structural problems has come at several costs, including rising wealth inequality, in turn leading to a polarisation in political parties.

Today, central bankers are under increasing political pressure globally – partly because of the collateral effects of their policies, which we have explained in detail – partly because of the lack of simple political alternatives. Recent appointments, like Mr. Powell at the Fed or Ms. Lagarde at the ECB, confirm that central banking is no longer exclusively the realm of a small group of PhD economists – in the past, many coming from the same schools (Mario Draghi, Mervyn King, Stanley Fischer, Ignazio Visco all studied and/or taught at MIT).

3. What are the limits?

If monetary policy is becoming less effective, the irony is that politicians and central bankers may respond with even more of the same. In a recent article, S. Edwards warned of “modern monetary disasters”, citing examples in Latin America as a potential scenario for governments pushing central banks out of their comfort zones.

In theory, interest rates are limited by the zero lower bound in the U.S. and by an economic boundary in the Eurozone, where we estimated at -1%, a level below which it would be cheaper for banks to hold cash physically than to keep it with the ECB.

However, central bank balance sheets could grow. The Fed and the ECB’s balance sheets continue to grow, yet at 19% and 40% GDP respectively, they are smaller than their global peers. The SNB and the BoJ balance sheets, for example, are already larger than the size of their respective economies.

4. Monetary policy 3.0

If current non-conventional policies have been a leap forward from traditional measures, the future political landscape could warrant an even more radical shift. A Democratic win in the U.S., for example, or a Labour win in the next U.K. elections could move the debate towards modern monetary theory, or QE for the people. Both ideas essentially postulate that central banks should print as much money as needed to bring the economy at full employment. While one could argue some advantages vs buying financial assets, which has a mechanical impact on wealth inequality – the continued use of monetary tools to fix structural economic issues like lack of productivity, declining competition and investment is worrying.

In some cases, as we have also shown, persistent low interest rates can be self-defeating, encouraging banks to hoard capital or investing it in sovereign bonds; favoring industry consolidation and reducing competition.

However, one lesson we have learnt as investors is that policymakers are not rational. The simple fact that one remedy will not work to heal the patient does not mean it won’t be used. Especially in a shift from centre-right to radical leftist governments, the potential for monetary policy 3.0 to happen is large.

Conclusions: Navigating QE Infinity

For fixed income investors, a return to QE is a temporary boon but creates a long-term drought in returns. Investors are forced to live in a yield desert, with only a few attractive areas offering rewards, and many traps – including highly leveraged firms offering little premium for their risk. In a potential race to the bottom, developed central banks could devalue their currencies against hard assets and EM currencies, which offer much larger real yields.

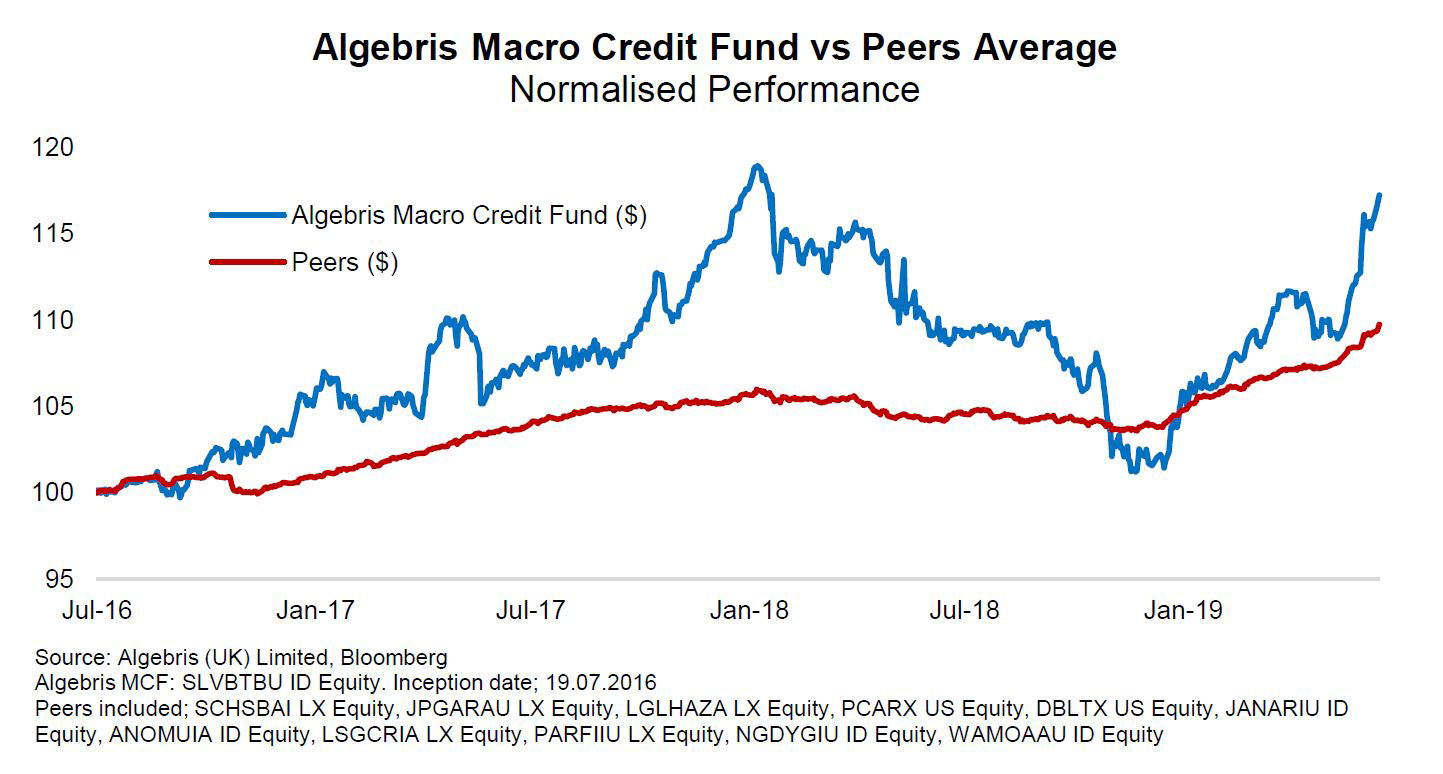

We are positioned to benefit from this environment, thanks to the degrees of freedom offered by our liquid macro credit strategy.

We entered 2019 long risk in credit and long rates, on the view that investors were over-pricing recession risks and central bankers were likely to start an easing cycle. Our view has mostly played out in H1 and we have taken partial profits. We enter H2 selectively long risk, with capacity to add risk into market weakness.

In rates, we had been long duration not only in the United States, but also in countries where private debt imbalances will require rates to stay low for a prolonged period of time, in our view: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Sweden. However, we have now taken profit on all our DM rates, following the strong rally and as investors consensus expectation has shifted to a prolonged period of low rates. We have also partially reduced our exposure in EM rates longs but keep long duration in selected emerging markets still offering high real rates against stable inflation: Mexico, Indonesia and Ukraine.

In credit, we have taken significant profits on our gross long credit position, but we remain positioned pro-beta, given the record-high differential between investment grade and double-Bs high yield paper. In other words – “safe” credit is already expensive, and not necessarily safe at these prices, in the case of a really bad scenario. We remain long credits with catalysts or those than have underperformed, like Pemex, where the Mexican government is likely to push for a new industrial plan. We are also increasing our tactical shorts in cyclical firms with leveraged, complex capital structures and limited access to equity financing.

In FX, we are overweight EM currencies where central banks have been hawkish in the past, but have room to migrate to more dovish policy.

In equities, we maintain a small short bias, particularly among stocks with leveraged capital structures, as we do not foresee an acceleration in earnings.

We believe flexible, liquid active strategies are well positioned to outperform in this environment of generally low volatility, where markets don’t always distinguish the fundamentals of different countries and sectors.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Algebris e i suoi prodotti o per farsi inserire nella lista di distribuzuione, si prega di contattare il dipartimento Investor Relations all’indirizzo algebrisIR@algebris.com. Gli articoli passati sono disponibilii sul sito Algebris Insights

Questo documento è emesso da Algebris (UK) Limited. Le informazioni contenute nel presente documento non possono essere riprodotte, distribuite o pubblicate da alcun destinatario per qualsiasi scopo senza il preventivo consenso scritto di Algebris (UK) Limited.

Algebris (UK) Limited è autorizzata e regolamentata nel Regno Unito dalla Financial Conduct Authority. Le informazioni e le opinioni contenute nel presente documento hanno solo scopo informativo, non hanno la pretesa di essere complete o complete e non costituiscono una consulenza in materia di investimenti. In nessun caso qualsiasi parte del presente documento deve essere interpretata come un’offerta o una sollecitazione di qualsiasi offerta di qualsiasi fondo gestito da Algebris (UK) Limited. Qualsiasi investimento nei prodotti cui si fa riferimento nel presente documento deve essere effettuato esclusivamente sulla base del relativo Prospetto informativo. Queste informazioni non costituiscono una Ricerca di Investimento, né una Raccomandazione di Ricerca. Con il presente documento Algebris (UK) Limited non organizza o accetta di organizzare alcuna transazione in qualsiasi tipo di investimento, né intraprende alcuna attività che richieda l’autorizzazione ai sensi del Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

Non si può fare affidamento, per nessun motivo, sulle informazioni e sulle opinioni contenute nel presente documento, né sulla loro accuratezza o completezza. Nessuna dichiarazione, garanzia o impegno, esplicito o implicito, viene data in merito all’accuratezza o alla completezza delle informazioni o delle opinioni contenute in questo documento da parte di Algebris (UK) Limited , dei suoi direttori, dipendenti o affiliati e nessuna responsabilità viene accettata da tali persone per l’accuratezza o la completezza di tali informazioni o opinioni.

La distribuzione di questo documento può essere limitata in alcune giurisdizioni. Le informazioni di cui sopra sono solo a titolo di guida generale ed è responsabilità di ogni persona o persone in possesso di questo documento informarsi e osservare tutte le leggi e i regolamenti applicabili di qualsiasi giurisdizione pertinente. Il presente documento è destinato esclusivamente alla circolazione privata per gli investitori professionali.

© Algebris (UK) Limited. Tutti i diritti riservati. 4° Piano, 1 St James’s Market, SW1Y 4AH.