The QE party is ending. Last year’s Goldilocks global expansion has left the way to an environment of divergence, where the US continues to outperform the rest of the world and the Federal Reserve is the only central bank no longer behind the curve on policy normalisation.

At the beginning of the year, we prepared for an environment of benign divergence, where the distribution of global growth would become increasingly skewed in favour of the US, yet still remain positive elsewhere. Today, this is worth reconsidering. While our base case scenario is still positive, volatility is returning to markets, and one by one some of the most vulnerable economies are being tested: Argentina and Turkey in emerging markets, Italy and Spain in developed markets.

Are these crises idiosyncratic events, or signs that the global recovery is about to turn into a broader slowdown?

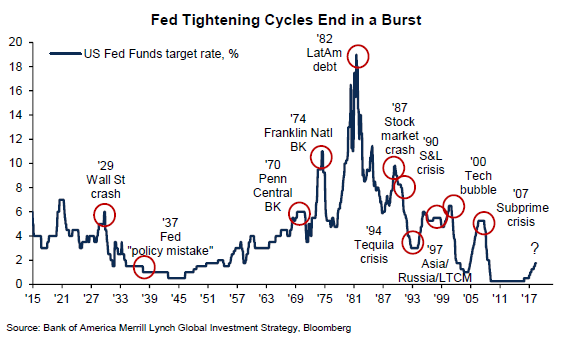

The standard explanation for the repricing in risk premia we are experiencing is the withdrawal of central bank liquidity by the Federal Reserve. Historically, this has coincided with unwind of carry trades and bursting of financial asset bubbles, as shown below.

That said, there are peculiar characteristics which make this tightening cycle different from others: asset overvaluation, rising wealth inequality and misallocation of resources resulting from persistent low/negative interest rates. On the one hand, we believe these overhangs will make withdrawal of stimulus trickier for central bankers. On the other hand, they will make a potential future slowdown more difficult to navigate for investors.

Why are financial markets more fragile?

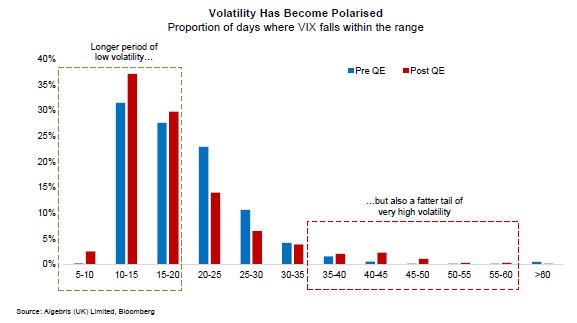

With asset prices influenced by central bank demand and investors accustomed to ten years of extraordinary stimulus, we have evidence of increased fragility. One area of fragility is trading liquidity in equity and bond markets, which has become scarcer as asset managers have taken higher risks and banks have re-trenched due to tighter regulation. Since 2007, equity and bond markets have experienced at least eight flash crashes. While the median level of volatility is lower than the pre-QE period, the magnitude of volatility shocks is larger. Put differently, markets are alternating between longer periods of calm and sharper, more sudden shocks. Adding to the lack of trading liquidity and polarisation of volatility shocks are passive and quantitative-driven trading flows, which now account for over half of all equity trading flows, and which can also exacerbate downward moves. Scarce liquidity and herding both act as feedback loops, amplifying shocks in what H. Minsky first described as financial fragility.

If financial markets are more fragile, they are also still linked to the economy. Monetary easing relied on a positive wealth effect from rising asset prices, as the BIS has pointed out in several papers. The question is whether asset price shocks may eventually defeat the initial purpose of monetary easing, and push policymakers to lower interest rates again.

How would a slowdown look like this time around?

No one owns a crystal ball predicting markets and the economy. Our base case scenario is for growth to continue to be positive, as confirmed by recent data in Europe and the US, and for inflation to move towards its target in the US and (more slowly) in other developed economies. However, after one of the longest recoveries in history, it is useful to run a hypothetical exercise.

We imagine how a slowdown would hurt the economy, think about policymakers’ reaction functions, and draw investment conclusions. There are some key differences between today and 2007:

1. Monetary ammunition is limited. Even though the Federal Reserve has some room to normalise policy, other central banks are having a much harder time due to still-high youth unemployment and high periphery spreads (ECB), low inflation (BoJ), a property bubble and the stagflationary effects of Brexit (BoE). The risk is that some of these central banks may have entirely missed the exit train, as we discussed in our last Silver Bullet.

2. Debt overhangs remain large. US high yield corporate debt ($2tn); UK consumer debt (£300bn); sovereign debt in Italy, Portugal and Greece; local debt in China are some of the largest debt overhangs which have either remained large or grown during the crisis. However, leverage has also grown in countries which were previously considered safe havens, and that lived through the crisis largely unscathed. These include Sweden and Canada, where property markets have risen exponentially together with household and bank leverage, and Australia, whose dependence on China’s economy and commodity exports combines with property overvaluation.

3. Policymakers’ reaction functions are likely to be more extreme and idiosyncratic, depending on each country’s political environment. Put differently, we think any global slowdown in growth is unlikely to be met by a coordinated emergency monetary policy stimulus. Instead, each country will likely calibrate a fiscal reaction depending on its available headroom, but also on economic and social issues. In the UK, for instance, should Labour win the next General Election, then universal basic income and monetary financing of infrastructure may be raised on the agenda, helping to reduce record-high inequality and low real wages. The Eurozone’s situation is far more complex. One ideal response could be for core European countries to use accumulated fiscal reserves to stimulate growth and build much-needed infrastructure and defence capabilities. Italy and Greece, however, which have suffered a relative disadvantage from high currency levels and still not completed all the necessary reforms, may be tempted to use pro-growth measures beyond the point of fiscal sustainability.

What has changed across policymakers’ reaction functions?

One common fallacy for economists is to consider only aggregate variables for growth, debt, unemployment, and so on. The wave of quantitative easing liquidity did not lift all the boats equally: as it retreats, some will have benefited a lot more than others. The distribution of wealth, unemployment and growth today is different vis-à-vis what it was before QE. The gap between the haves and have-nots, large cities and rural peripheries, and between the old and the young has widened. While this has benefited luxury goods firms, it has also generated a general desire for political change. Protest politics are spreading, and after the US and UK, Italy and Spain have also switched to coalitions for change, promising far-reaching policies at little cost for the electorate.

As we wrote over the past years (The Silver Bullet | Investing in Times of Populism), the political move towards a much needed redistribution of wealth and opportunity makes a repeat of monetary stimulus unlikely, as a one-size-fits all tool to fight future economic slowdowns.

1. Monetary policy is likely to become more constrained and less independent. It has already become visible in some emerging markets (e.g. Turkey), but the same could happen in developed markets, as per the QE for the people initiative in the U.K.

2. Fiscal policy is likely to produce larger deficits, with a focus on wealth redistribution and support for poorer households. Italy’s proposals for a flat tax and universal basic income are a case in point.

3. International relations are likely to become more conflictual. We are experiencing trade renegotiations between the US and Europe, NAFTA and China. The potential for this to escalate into a trade conflict or a global trade war should not be underestimated. Geopolitical risk is also likely to stay high, with OPEC countries needing higher oil prices to diversify their economies, and Israel-Iran tensions likely to continue.

How can investors navigate this environment?

Since the end of last year, we flagged that policy normalisation by the Federal Reserve could come in tandem with renewed volatility in markets. As a result, we have gradually shifted our portfolio construction in the following direction:

1. Better liquidity. We have reduced the amount invested in cash bonds and substituted derivatives, including credit default swaps, as a tactical long (or short) instrument.

2. Barbell strategies and dry powder. We have increased the amount of liquid ‘dry powder’ instruments, creating a barbell between risky and risk-free assets.

3. Shorts. We have increased our directional shorts vs. what we think are some of the weakest firms and economies. We think Emerging Market debt remains vulnerable to a repricing, particularly in Brazil and Mexico, both of which face elections this year. Triple-B rated corporate bonds which have benefited from ECB purchases may also widen.

4. Tail hedges. We have increased the amount of hedges for bigger tail events, using convex instruments like mezzanine tranches or options contingent on a change in correlation regime, for example between currency and equities, or between equities and interest rates.

Our Macro Credit Fund remains biased towards positive yield positions across the remaining attractive areas of macro and credit markets, while hedging risks and at times switching to a net short exposure.

On June 1st, 2018, we launched the Algebris Tail Risk Fund, a strategy dedicated to offering investors protection in market shocks, which will leverage and expand our macro short positions.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Algebris e i suoi prodotti o per farsi inserire nella lista di distribuzuione, si prega di contattare il dipartimento Investor Relations all’indirizzo algebrisIR@algebris.com. Gli articoli passati sono disponibilii sul sito Algebris Insights

Questo documento è emesso da Algebris (UK) Limited. Le informazioni contenute nel presente documento non possono essere riprodotte, distribuite o pubblicate da alcun destinatario per qualsiasi scopo senza il preventivo consenso scritto di Algebris (UK) Limited.

Algebris (UK) Limited è autorizzata e regolamentata nel Regno Unito dalla Financial Conduct Authority. Le informazioni e le opinioni contenute nel presente documento hanno solo scopo informativo, non hanno la pretesa di essere complete o complete e non costituiscono una consulenza in materia di investimenti. In nessun caso qualsiasi parte del presente documento deve essere interpretata come un’offerta o una sollecitazione di qualsiasi offerta di qualsiasi fondo gestito da Algebris (UK) Limited. Qualsiasi investimento nei prodotti cui si fa riferimento nel presente documento deve essere effettuato esclusivamente sulla base del relativo Prospetto informativo. Queste informazioni non costituiscono una Ricerca di Investimento, né una Raccomandazione di Ricerca. Con il presente documento Algebris (UK) Limited non organizza o accetta di organizzare alcuna transazione in qualsiasi tipo di investimento, né intraprende alcuna attività che richieda l’autorizzazione ai sensi del Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

Non si può fare affidamento, per nessun motivo, sulle informazioni e sulle opinioni contenute nel presente documento, né sulla loro accuratezza o completezza. Nessuna dichiarazione, garanzia o impegno, esplicito o implicito, viene data in merito all’accuratezza o alla completezza delle informazioni o delle opinioni contenute in questo documento da parte di Algebris (UK) Limited , dei suoi direttori, dipendenti o affiliati e nessuna responsabilità viene accettata da tali persone per l’accuratezza o la completezza di tali informazioni o opinioni.

La distribuzione di questo documento può essere limitata in alcune giurisdizioni. Le informazioni di cui sopra sono solo a titolo di guida generale ed è responsabilità di ogni persona o persone in possesso di questo documento informarsi e osservare tutte le leggi e i regolamenti applicabili di qualsiasi giurisdizione pertinente. Il presente documento è destinato esclusivamente alla circolazione privata per gli investitori professionali.

© Algebris (UK) Limited. Tutti i diritti riservati. 4° Piano, 1 St James’s Market, SW1Y 4AH.