“The lesson of history, then, is that even as institutions and policy makers improve, there will always be a temptation to stretch the limits. Just as an individual can go bankrupt no matter how rich she starts out, a financial system can collapse under the pressure of greed, politics, and profits no matter how well regulated it seems to be.“

Carmen M. Reinhart, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly

There’s an eerie mood among investors. The feeling that even with a multi-trillion fiscal and monetary stimulus, the recovery may rest on fragile foundations. The idea that even with many asset classes back to positive returns this year, sooner or later, there may be a price to pay for everyone.

At the core of the problem is the fact that while financial markets have been hitting new highs, the economic, social and political foundations the current equilibrium rests upon appear shaky.

First, the virus hit poorer regions harder, while top-down fiscal and monetary stimulus does little to reduce inequality. Monetary policy alone does not guarantee lasting prosperity for our economies, as Mr Draghi said months after the launch of QE, in 2015. After a decade of monetary stimulus pushing stocks higher but leaving real wages stagnant, there is fertile ground for social unrest.

Second, in an attempt to gain electoral support, governments are increasingly taking control of money supply. This includes considering stronger forms of debt financing and financial repression, like negative interest rates in the UK or yield-curve-control in the US.

Third, even though Covid-19 may be contained in China and most European countries, the risk of a flare-up in contagion remains high, with many economic sectors likely to take deep scars from persistent lack of demand.

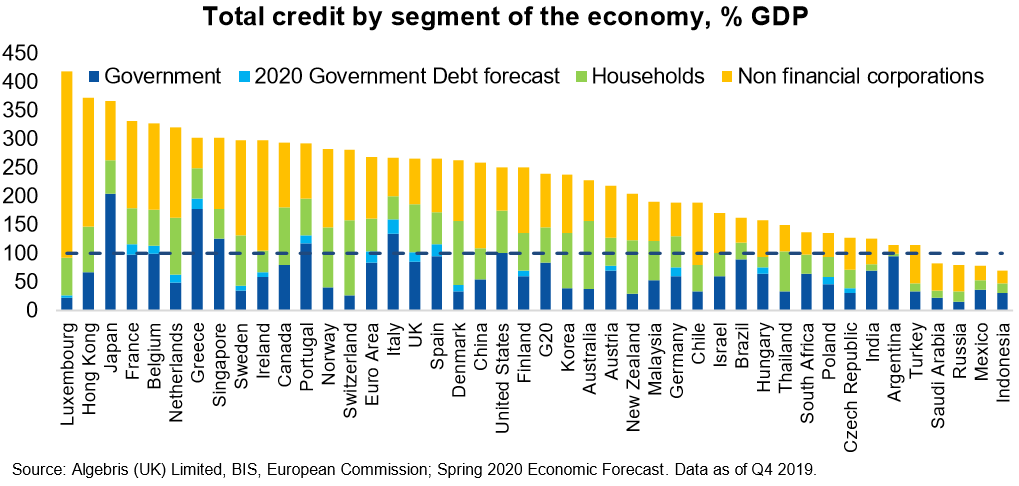

This is why underneath the apparent calm in financial markets, larger changes to the current economic and social equilibrium may be looming. Debt-based democracies relying on low interest rates and let-them-eat-credit subsidies to appease voters may be tempted to stretch the limits, through even larger deficits and asset purchase programmes. Inflation is not only a monetary phenomenon, it is firstly social and political: voters are angry. Investors holding $70tn of global government debt at near-zero or negative yields may soon realise they are boiling frogs, exposed to any small rise in long-end interest rates, or to persistently negative real yields.

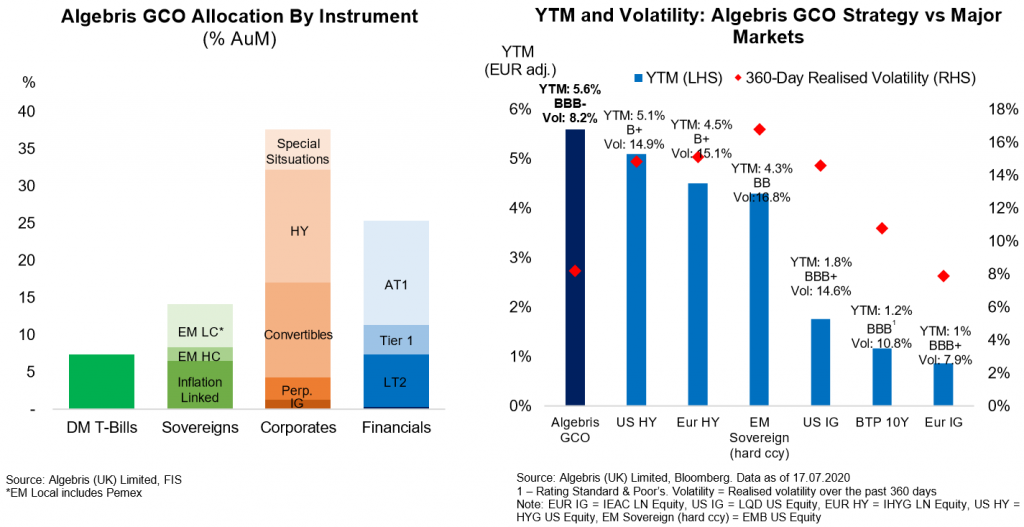

Sooner or later, the boiling frogs may have to jump into other assets. Our fund, renamed Global Credit Opportunities at its fourth birthday to highlight value in credit, is now positioned across fixed income alternatives, including inflation linked debt, convertibles, credit and gold. We are also overweight Europe, where we think the new €750bn stimulus plan represents a gamechanger amid a backdrop of cheaper asset valuations.

Covid-19: An Uneven Recovery

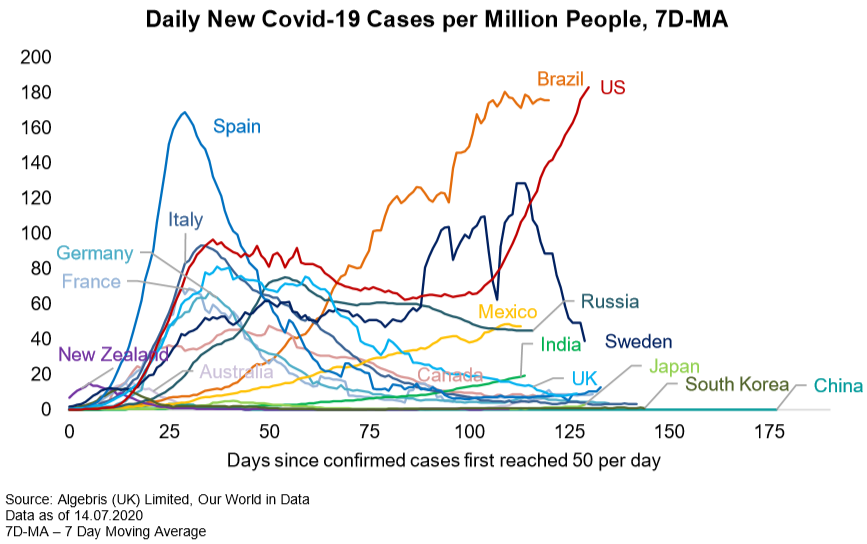

Worse virus control is impeding the US’s economic recovery. The pandemic hit Europe harder initially, where countries saw faster virus spread and more casualties. Being forced to adopt more stringent lockdown measures, European countries in general experienced a bigger dip in economic activity in March-April. However, a faster response to the virus also allowed Europe to better control its outbreaks and recover faster: despite continued progress in economic reopening, new infection rates have remained low.

In contrast, countries with slow or uncoordinated responses to the virus might have avoided a deeper slump at the start, but are now suffering from slower recovery, like the UK or Brazil, or a stall in recovery due to resurging cases, like the US

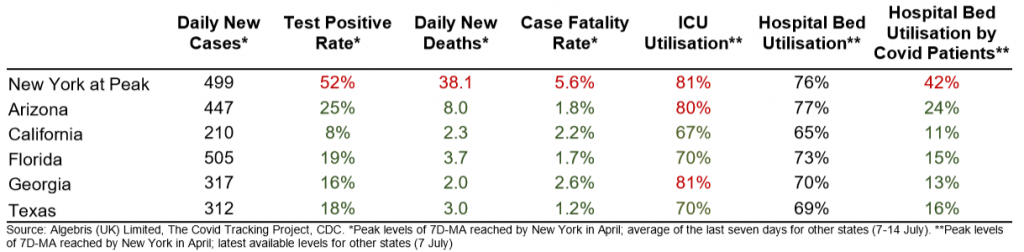

In the US, a second round of outbreaks across southern states have pushed daily new cases to new highs. Compared to the first round there are some positive observations: despite higher daily new cases, hospital occupancy by Covid patients and death rates have remained much lower so far, as shown below. This could be due to earlier case detection given wider testing, improved knowledge about effective treatments and reportedly better patient demographics. A less stressed medical system and lower death rates might have reduced the need for drastic nationwide lockdowns again, but continued case growth inevitably slows down the country’s economic recovery. We are already seeing signs of stagnation in a range of real-time data we track, including mobility, consumer spending, small business opening and restaurant diners. Moreover, such stagnation seems to be broad-based and is observed even in states with low case growth. It could be that the fear factor is also at play, leading people to change behaviours voluntarily without official restrictions.

United States: A Cure Against Populism?

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

Isaac Asimov, 1980

In a 1980 piece published by Newsweek and titled ‘the cult of ignorance’, science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov lamented what has become more relevant over the years, and not only for the United States. In our past Silver Bullet investor letters, we anticipated that the sharp post-crisis rise in inequality would have provided fertile ground for populism.

We identified populist governments by three common characteristics: proposing an unrealisable dream – like returning the US to its industrial might or achieving Brexit without paying for it – polarising the population’s anger against an enemy, and implementing unsustainable economic policies. In the historical analysis by Dornbusch and Edwards, populist governments eventually hit bottlenecks and crises. It is possible the virus may have accelerated the course of events, and that today we may be witnessing a silver lining from the Covid-19 epidemic, which highlighted the limits of slogan-rich but planning-poor governments.

Democrats could win the election. We think the impact to risk-assets would be better than expected. There is a high probability that Biden may win the US elections in November. Never before has the incumbent President’s approval rating lagged their opposition to this extent: Trump is lagging nearly 9pts behind Biden in the polls. Additionally, polling indicates that Biden is leading even amongst swing states like Florida, Michigan and Arizona. While Biden’s VP nominee and senior appointments like the Treasury Secretary are yet unknown, our expectation is that a Biden government will be positive or neutral for risk-assets – given a lighter focus on reverting corporate tax cuts and a stronger focus on fiscal expansion.

As Biden has already begun to articulate in his campaign trail, his policies will likely be expansionary, supporting jobs in labour-intensive industries like manufacturing and a $2tn green energy and infrastructure plan. We expect a Biden administration to be more supportive of trade-relations with Mexico, Canada and the EU, while we think they would continue trade pressures against China, though likely in a less erratic or confrontational manner.

Rather than a Democratic win, a key risk from the US elections could be a delay in the vote count, lengthening the period of uncertainty and the opportunity for Trump to contest the results. This delay could be on account of the rise of postal-voting: 2/3rds of Americans have said they are in favour of postal voting in this environment, which could lengthen the time vote count by a few weeks.

Virus numbers are worsening and the economy could falter, but the Fed will be ready to act. While the US economy is still below its pre-COVID level, the economy has fared much stronger than feared by investors as demonstrated by the Citi economic surprise index. In part, this economic outperformance is explained by the large stimulus in the US, which thus far has totalled $3tn or 14% of GDP. Additionally, the Fed’s strong action has eased financial conditions, which has kept corporate bond markets open, allowing companies to finance their deficit needs at low-levels. Looking forward though, the outlook for the US economy is less clear.

Firstly, the course of the virus remains a key variable. Despite a re-opening of the economy, as the infection numbers have risen, consumer-focused businesses have seen a stall in activity. Retail traffic since openings are levelling-off near -40% YoY at the end of June, airlines are seeing demand at -60/-70% YoY and mobility data indicates a plateauing too.

Secondly, with upcoming elections, the government is unlikely to sanction new fiscal expenditure, meaning eventually the existing stimulus will wear-off and the COVID-cheques will get spent. However, to counter these economic uncertainties, we expect the Fed to remain dovish and be ready to do more if needed. We noted the Fed’s strong back stop when in June, on slight market weakness, the Fed amended their corporate bond purchase program to make it easier for them to purchase, following which they have been buying an average of $200mn in corporate bonds per day, as of the 8th of July.

Market implications: we position for USD weakness and remain long only in pockets of credit. We believe we may be towards the end of the US’s multi-decade economic exceptionalism, which has been a strong factor contributing to USD strength. US rates are nearly as low as other DM rates: the Fed, while avoiding negative rates, has cut rates to the bone.

US politics are departing from their traditional forms of capitalism and moving closer to values seen more closely in Canada, the EU and other DM democratic economies. And, stripping away the tech sector, US corporates are performing in line with their global peers. Regarding credit, US HY credit is near its all-time wide relative to EU HY. In part, this has been because there have been almost no European defaults in comparison to the US: In the European Xover index, the default rate is under 4% vs 7% in the US CDX HY index.

In the US, we like sectors which have experienced a sharp recovery (like autos) and select issuers either with a positive-catalyst or strong government support like Adient and Ford. However, more than directional longs, we like selling deep out-of-the-money credit puts which offer very attractive risk-adjusted returns despite their significant distance from current levels and the strong likelihood of expanded Fed support in another round of market weakness.

Europe: From Unloved to Rising Star

Against a persistent euro skeptic narrative, Europe is proving more resilient than many investors thought before. The same features which have made EU economies less competitive during boom times – including less flexible job markets, higher taxes and a stronger social security system – are helping to reduce downside risks during the crisis. The EU’s resilience has been noted by European citizens, with most European leaders’ approval rating rising during the crisis, unlike for the US.

After Britain’s exit, we see a chance for Europe to become more integrated. EU leaders have negotiated a €750bn fiscal package, with €390bn in grants and €360bn in loans. The most salient feature of this package is that it will be partially funded through a common EU budget – a significant step towards closer EU fiscal integration.

An agreement was reached following weeks of negotiations, where the main points of debate were between the frugal four (Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark) and other member states. The frugal four raised concerns on directing the funds appropriately and achieving the right funding mix – a reasonable concern – as well as attempted to reduce the size of the package and introduce veto power for single countries. We believe the last point would have been a deal-breaker, as it would put one country’s domestic parliament above EU common rules, i.e. against the principles of the Lisbon Treaty. In the agreed deal, the frugal four managed to get the grant component reduced to €390bn from the €500bn initially proposed and secured higher budget rebates. However, single countries’ veto power was not introduced. Member states’ spending plans will be assessed by the Commission and approved by the Council by qualified majority. Individual countries can raise concerns about member states’ “serious deviations” from fulfilling relevant milestones and targets to the Council, which will need to decide within three months.

Adding to the urgency of the package were the economics in favour of Southern Countries. Unlike the frugal four’s narrative, EU contributions have been flowing West to East, not North to South. Southern Countries have been net contributors, on aggregate, with Italy paying over €60bn to the EU over the past two decades. Conversely, the Netherlands, who leads the frugal four coalition, is among the top ten tax havens globally: Tax Justice Network calculates that France, Germany, Italy and Spain lose around €10bn a year to Dutch tax authorities. A tax equalisation is therefore a necessary and long-awaited step, although it may be delayed further, with Irish candidate Donohue winning the Eurogroup Presidency.

Overall the negotiation saw the typical twists and turns but eventually approval of a package was reached which would make all leaders be able to say they have fought hard enough to protect the interest of their citizens – Dutch PM Rutte faces elections next March. Europe’s path towards further integration remains bumpy but there is progress which would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Market implications: we expect a stronger EUR, stable European credit spreads and higher European stocks. We expect the EUR to be higher with stronger fiscal support, greater EU integration and DM central bank rates converging to the ECB’s or hinting at negative rates. With DM central banks cutting rates but the ECB remaining on hold, the opportunity cost of holding Euro relative to other currencies is no longer as penalising to investors. Furthermore, in combination with the falling risk of a euro-breakup scenario and falling support for populists in Europe, investors may be more comfortable holding EUR vs other currencies. Investors converting their currency into Euros may also look to hold European assets. While European credit spreads look tight relative to the US, they remain well anchored by the ECB asset purchase programs, and by lower corporate leverage. Additionally, European equities look attractive and remain cheap vs their global peers.

EM – Keeping it Selective

We stay selective on emerging markets debt as the asset class sends mixed signals. Most of the large countries struggling to contain the virus are in emerging markets, with Brazil, Mexico, S. Africa still experiencing volatility in the number of cases. This leaves the door open for further reductions in growth forecasts. On the other side, fundamentals have improved since March. Weaker currencies triggered a quick external adjustment, and activity has bottomed in May. Lower UST yields and local central bank cuts have eased financial conditions substantially, strongly benefiting both local and hard currency bonds. Some country are engaging in QE-like programs, but sizes are very small compared to developed markets.

We favour hard currency over local markets. USD spreads are still wide and supported by the Fed, while low local rates leave FX volatile. In hard currency we remain constructive on countries which made stabilisation efforts before Covid, like Egypt and Ukraine, or welldiversified commodity exporters, like Ghana. Government-owned energy producers enjoy the upside from oil recovery and have limited downside thanks to public support. The selloff opened opportunities in a high quality telecom issuer and government-owned airlines in specific jurisdictions. In local markets, Russia and Indonesia have been punished despite good fundamentals. In Turkey, markets remain stable despite a sharp deterioration in the country’s financial position. We think this divergence may come to an end in the next few months.

China, the Year of the Rat turning better. News out of China remains relatively positive. Activity has rebounded sharply since March, with PMIs back in expansion territory and durable sales catching up quickly to their pre-lockdown levels. Virus numbers remain in control. Tensions with US seem to have moved from trade to diplomatic territory, which leaves open the long-term issue but limits economic damages before US elections. The recent equity market rally looks excessive in some sectors but underlines a positive tone of domestic investors and a structural under-positioning in non-US assets. Monetary policy remains substantially tighter than the rest of the world. We see select value in China real estate bonds. Moreover, robust activity and tight CNY policy are likely to contribute to outperformance of non-US equities and to potential for US dollar weakness.

Inflation – A Social and Political Phenomenon

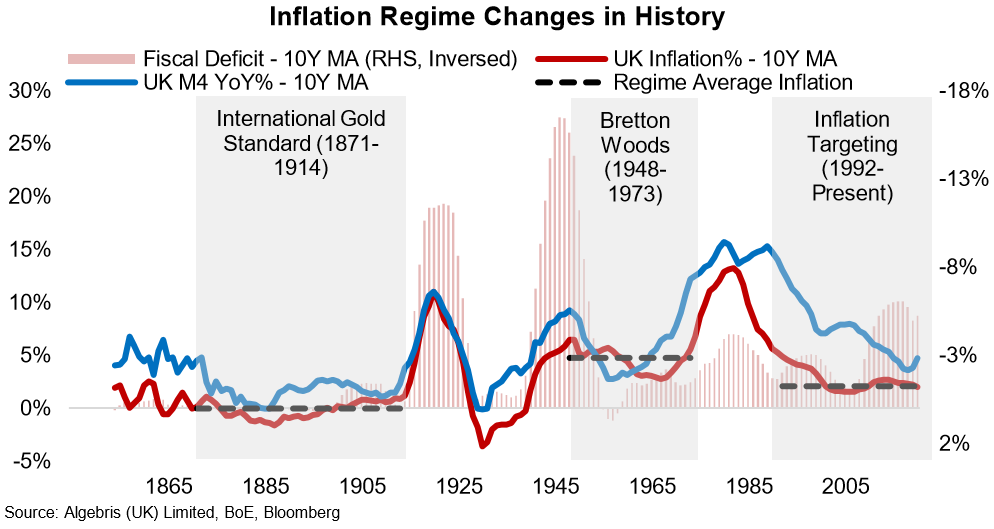

Economists are struggling with inflation forecasting. After decades of tight labour markets and low domestic slack together with loose monetary policy, traditional monetary theory and the axiom that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” are under pressure.

There are several reasons why old inflation models based on slack and unemployment no longer work: globalisation, technology, slower demographics, lighter power of unions, monopolistic supply-side behaviour, weak banking sectors unable to transfer monetary stimulus. Economists – see recent papers by the BIS and ECB – have acknowledged that domestic factors are playing a minor role than before, and that the Phillips Curve has flattened.

That said, central bankers have so far reacted to this lowflation environment doing more of the same: keeping interest rates at record lows, and raising asset purchases to record highs. This resulted in what we have described as the QE Infinity Trap, a perpetuation of monetary stimulus which becomes increasingly ineffective yet still needed at each attempt. There are various reasons why persistent QE and negative interest rates become ineffective over time, which we can group into:

- Demand-side distortions: consumers realise they have to save more to afford retirement;

- Supply-side distortions: companies hoard cash and invest less and/or consolidate more easily thanks to low rates, reducing competition. Banks become defensive due to low interest rates and profitability and shun risky loans, hoarding sovereign debt or mortgages;

- Asset-price distortions: sectors which are leverage-heavy, like real estate or finance, or growth companies, receive more capital. This, in turn, creates asset bubbles and a potential boom-bust cycle.

So far, QE Infinity, i.e. persistent low interest rates and asset purchases have failed to lift off inflation, absent other policies to stimulate growth.

However, a look at history shows that sudden external or policy shocks can cause a break from a stable inflation environment. In the case of the UK, inflation has accelerated in history, following large pick-ups in money supply growth, accompanied by multi-year fiscal expansions. But these regime changes were also a reflection of political and social movements, as highlighted by P. Bernholz’s Monetary Regimes and Inflation.

Today’s policy responses reflect a social and political regime change. Electorates in developed countries are angry. The virus is the culprit, but behind protesters from Portland to London is the asset-rich but wage-poor recovery of the past decades, which benefited large firms but left middle classes and suburbs behind. Governments are pressed to find a solution.

Money to the people. First, governments are taking control of the money supply. This means less central bank independence and more aggressive monetary policy: the Federal Reserve has been discussing a shift to a higher inflation target of 2.5% as well as average inflation targeting, while the Bank of England is considering negative interest rates. Second, fiscal policy is aggressively accompanying monetary stimulus with record deficits. Third, both fiscal and monetary policy are increasingly engineered to stimulate individuals and SMEs, rather than raise the price of already-inflated assets: half of the $3tn US fiscal stimulus has been directed to individuals and SMEs, while the Federal Reserve SMA facility has provided credit to small businesses for the first time – in addition, governments around the world have extended furlough, universal basic income or other subsidies to individuals. This is helicopter money.

We believe many of these shifts in policy will be permanent, and have the potential to eventually cause a shift in inflation regime.

The pace of monetary expansion since March has been higher than any intervention over the past twenty years, and most of the new cash in circulation is now reaching the middle-class, not only pushing asset prices up and benefiting the top one percent earners, as before. As poorer households have a higher propensity to consume, the ground for inflation is more fertile than ever. These could be coupled with an acceleration of the de-globalisation trend, which had already emerged before Covid-19.

Priced for perfection. Against this backdrop, pricing across rates markets appears vulnerable. The wipeout buffer, the amount of spread or rates widening sovereign and investment grade bonds can withstand, is at record lows. For triple-B corporate bonds, only a 50bp widening in rates is enough to wipe out a year of carry.

Financial repression. History tells us that when faced with epochal changes, governments use their currencies as an instrument for survival, and currencies lose the capacity to preserve wealth. Central banks’ QE infinity failed to lift off inflation over the past two decades. Today, governments hard-pressed by social unrest and inequality are likely to resort to extreme monetary measures, coupled with helicopter-like fiscal stimulus. The result may be orderly, with bondholders accepting yields well below inflation, or disorderly. In the first case, government bond investors will lose money slowly – in the second, they will lose it faster.

Conclusions: Buy Fixed Income Alternatives

“We have gold because we cannot trust governments“

Herbert Hoover

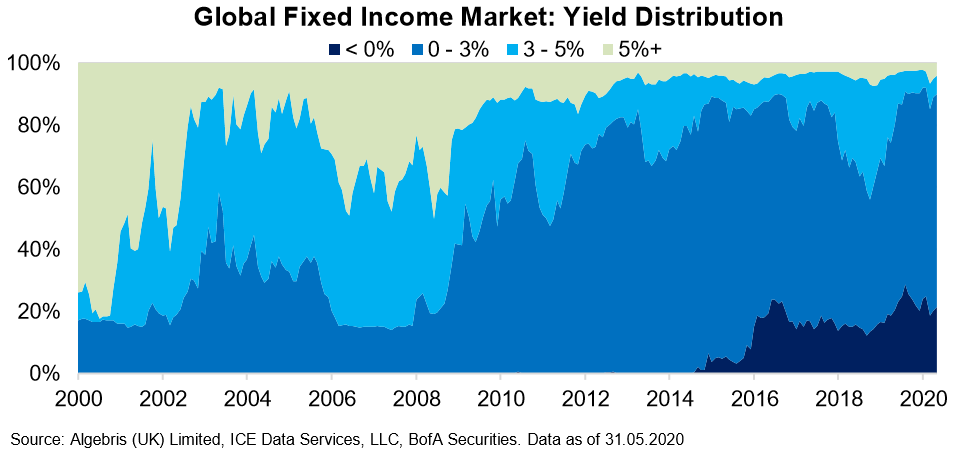

There is $70tn in government bonds globally. $12.3tn yield negative. Only 10% of global fixed income markets yield over 3%. Today’s monetary and fiscal stimulus is unprecedented in size and scope – and governments are taking control of money supply.

This brings us to a few conclusions:

- Central banks are likely to stay locked into stimulus for a long time, long beyond the official conclusion dates of their asset purchase programmes

- Governments will likely continue producing large deficits: both candidates for US elections have pledged fiscal stimulus to revive weak economic sectors and get electoral support. This stimulus is increasingly bottom-up, aimed at individuals and SMEs rather than large firms. This means spending is going to economic agents with more propensity to spend – and to vote, making it politically harder to withdraw it.

- Inflation is firstly a social and political act, before a monetary phenomenon. The rules of the game are changing: governments are taking control of the money supply. The Fed is likely to shift its inflation target higher, and other central banks will follow suit towards more drastic policies.

- Investors in government bonds are a boiling frog: the Covid-19 crisis has produced a deflationary reaction, but the capital gains in sovereign bonds will be hardly repeatable.

- We advise to diversify in alternatives that either generate higher yields, like credit, or protect against persistent low/negative real interest rates, like inflation-linked debt and gold, or offer upside in a better economic scenario, like convertibles.

Our Global Credit Opportunities strategy is at its fourth birthday. We have renamed it to highlight the opportunity in credit markets, while its strategy and management team are unchanged. Over the past few weeks, we have increased our allocation to inflation-linked debt, convertibles and maintain upside convexity in gold. In addition, we hold a portion of our book in idiosyncratic special situations in credit, which offer uncorrelated upside. In times of financial repression, we believe investors will need a dynamic, diversified strategy to defend their capital

For more information about Algebris and its products, or to be added to our distribution lists, please contact Investor Relations at algebrisIR@algebris.com. Visit Algebris Insights for past commentaries.

This document is issued by Algebris Investments. It is for private circulation only. The information contained in this document is strictly confidential and is only for the use of the person to whom it is sent. The information contained herein may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose without the prior written consent of Algebris Investments.

The information and opinions contained in this document are for background purposes only, do not purport to be full or complete and do not constitute investment advice. Algebris Investments is not hereby arranging or agreeing to arrange any transaction in any investment whatsoever or otherwise undertaking any activity requiring authorisation under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. This document does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of an offer to subscribe or purchase, any investment nor shall it or the fact of its distribution form the basis of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract therefore.

No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information and opinions contained in this document or their accuracy or completeness. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document by any of Algebris Investments, its members, employees or affiliates and no liability is accepted by such persons for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

This document is being communicated by Algebris Investments only to persons to whom it may lawfully be issued under The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 including persons who are authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 of the United Kingdom (the “Act”), certain persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, high net worth companies, high net worth unincorporated associations and partnerships, trustees of high value trusts and persons who qualify as certified sophisticated investors. This document is exempt from the prohibition in Section 21 of the Act on the communication by persons not authorised under the Act of invitations or inducements to engage in investment activity on the ground that it is being issued only to such types of person. This is a marketing document.

The distribution of this document may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. The above information is for general guidance only, and it is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this document to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. This document is suitable for professional investors only. Algebris Group comprises Algebris (UK) Limited, Algebris Investments (Ireland) Limited, Algebris Investments (US) Inc. Algebris Investments (Asia) Limited, Algebris Investments K.K. and other non-regulated companies such as special purposes vehicles, general partner entities and holding companies.

© Algebris Investments. Algebris Investments is the trading name for the Algebris Group.