“When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing”

Chuck Prince, former Citigroup CEO, July 2007

Everything in life is transitory. Duration, however, is what matters. This year’s inflation spike, driven by extreme base effects, will subside. But what will happen after the dust settles?

Some inflation drivers will indeed fade over time – supply chain disruptions, for example. Others might prove more persistent than we currently think. Rising geopolitical tensions mean developed countries will move towards onshoring production of strategic goods.

Ultimately, inflation is a political decision. Over the coming decade, millennials will become the median voter across developed countries. This means politics and policy will likely focus on appeasing a generation which has been left out from a decade of asset-based monetary policy and rising inequality. Milton Friedman used to say nothing is more permanent than a temporary government program. Having become popular, helicopter money might prove hard to cut down.

Complacency reigns across financial markets. The combination of record monetary and fiscal stimulus has given investors a double sugar rush since the COVID crisis, creating Paradise City-like valuations. Today, however, valuations are at extremes. Yield curves remain well below inflation, assuming central banks will continue record stimulus. Credit spreads are at record lows, assuming that even corporate zombies with record-high leverage will survive post pandemic. Volatility is at record lows, implying that tomorrow will be as good as today. Bubbles in cash-park, cashflow-less assets continue to grow. This includes art, collectibles like football rookie cards and cryptocurrencies, whose number has now swollen to over ten thousand. As negative real rates keep eroding the value of cash, investors are forced to buy riskier assets.

What happens when the music stops? Central banks in commodity driven economies have already rung the alarm bell. Canada, Norway, Mexico, Russia, Brazil, Hungary and the Czech Republic are on the way to reducing or have already reduced stimulus. In the United States, where fiscal stimulus has been greater and the recovery more advanced than most other developed markets, some central bankers are starting to break away from the dovish party line. With most states reopening as vaccinations rise, the pace and cost of job creation will be key to assess whether the Fed is behind the curve. We believe labour markets will be tighter post pandemic, with lower workforce participation and a need for higher wages.

In early 2020, we wrote that there was nothing left to buy, as valuations left very little on the table. As we all know, external events caused markets to topple shortly after. Today, the consensus narrative is one of a quiet summer and smooth sailing, while most investors appear on the same side of the boat. As a result, we believe markets are fragile and that even small changes in policy might trigger a repricing.

Will central bankers succeed in normalising policy – or fail as they did in 2018?

Inflation – a transitory spike followed by persistent bottlenecks

Headline inflation has risen globally and now exceeds 2% in most developed economies. Core inflation is also above historical averages. Transitory factors, like base-effects and supply-chain disruptions are contributing to the rise. The base-effects should pass before year-end as we exit last year’s weakest inflation period. Also, bottlenecks from chip shortages have caused prices to rise in end-products like cars and are estimated to increase core US CPI in 2021 by between 0.1% to 0.4%. While lead-times to source chips keep increasing, this shortage should eventually pass as production capacity is gradually added.

However, the Fed is now forecasting inflation to remain above its pre-pandemic lows for the next three years. At the Fed’s June meeting, they raised their core inflation forecast over the next two years to 2.1% and 2.2%.

The transitory inflation factors will eventually pass, but are there new persistent drivers for higher inflation? We think there are.

1. Real wage growth has lagged: wages will need to catch up

QE has fueled asset price inflation, but real wages have been eroded or barely risen across developed economies. Wages are now rising, and wage growth is above pre-pandemic levels in the US and Europe. On the one hand, this increase stems from workers’ reluctance to return despite record job openings. For example, strong wage growth in the hospitality sector is partly due to an undersupply of workers. As the pandemic-related support rolls off over the summer, we may see labor supply return and some wage normalization. On the other hand, political pressure for higher wages will likely continue. US political rhetoric is increasingly shifting towards tackling inequality, partly through fairer / minimum wage policies. President Biden recently reiterated this view by saying, “The simple fact is, though, corporate profits are the highest they’ve been in decades. Workers’ pay is at the lowest it’s been in 70 years. We have more than ample room to raise worker pay without raising customer prices.”

2. Commodity prices are structurally supported by stimulus and a lack of supply

Commodity prices have nearly doubled in 2020. This increase reflects a shift in the marginal buyer, away from China and towards the US. US demand for commodities is led by Biden’s push for infrastructure and green-transition spending, which was a major focus of his campaign. In response to the inflation from higher commodity prices, China has started to release its metal reserves. However, these measures can only help subdue prices temporarily.

For instance, China’s copper reserves are estimated at around 1.5-2m MT, which are significant relative to the potential deficits in 2021/22 of around 300-400k MT, but insufficient if the deficit continues to widen. Therefore, China’s action may constrain prices in the short-term, but in the long-term lower commodity prices need more metal supply, tighter monetary policy or lower infrastructure spending.

3. Onshoring of supply chains will increase production prices The global chip shortage has compounded inflationary pressures. While this shortage will pass and prices will normalize, probably over the coming year, the shortage has highlighted the risks of offshoring to the global supply chain. We expect increased onshoring of supply chains around strategic manufacturing goods – both as a lesson-learned from COVID, as well as a way to protect intellectual property in an environment of rising geopolitical risk. This de-globalization trend will increase redundancy and robustness of supply chains, but will likely increase production costs and potentially inflation. The OECD had estimated that the advent of globalization in the late 1990s decreased CPI by between a 0-0.25% per year, in OECD countries.

4. Governments will want higher inflation to deleverage their debt

Finally, governments are incentivized to pursue policies that stimulate inflation to reduce their stock of debt, boosted by the pandemic. Due to record fiscal stimulus, we estimate that developed economies have added between 10-20pp in debt to GDP in 2020, based on the IMF’s October WEO data. There are several ways to reduce this debt: promoting growth to outpace deficits, higher taxes, or even the nuclear option of a sovereign default. However, the most effective method to reduce sovereign debt historically has been persistent negative real rates. This was the case in the US post WWII, when a positive fiscal surplus was accompanied by higher inflation due to the removal of price controls and a continuation of war-time supportive monetary policies. On the contrary, following periods of high indebtedness in Canada and parts of Europe, higher nominal rates offset the benefits of higher inflation, leaving all the heavy-lifting to positive fiscal balances and higher real growth.

Central banks – breaking the dovish line

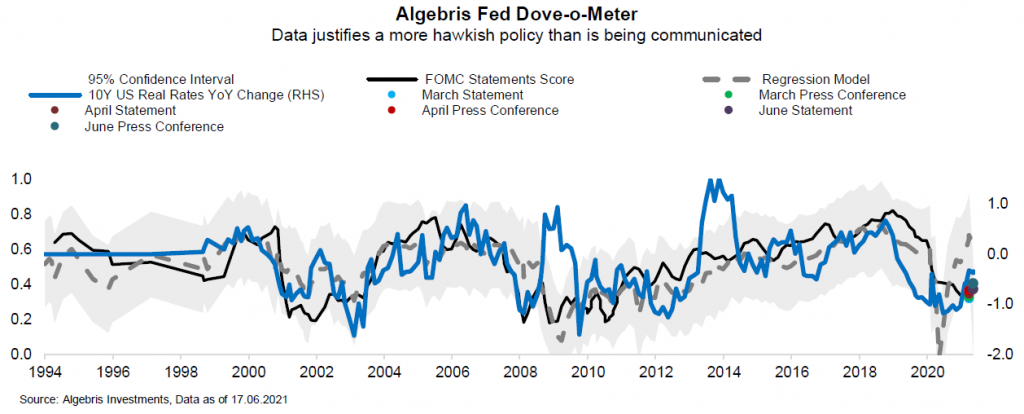

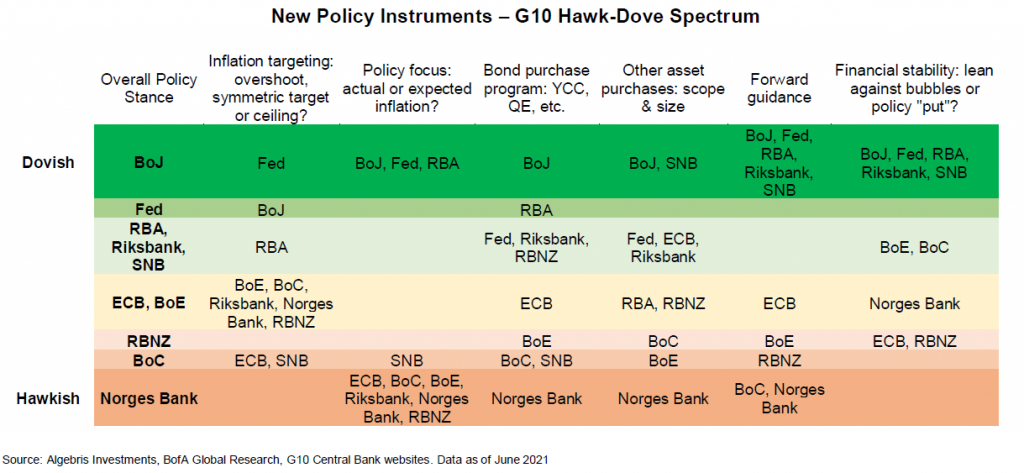

The Fed and ECB are pushing against tightening despite a strong economy and more permanent signs of inflation. At global level though, a few central banks are already taking hawkish steps: China’s PBOC keeps real rates positive, EM high inflation countries started hiking cycles, and other developed markets – Canada, Norway, New Zealand – are already more hawkish than the Fed. We think it is a matter of time for the Fed to follow. Summer should bring further strength in labour markets, so Jackson Hole could represent a hawkish pivot. In addition, the Fed and ECB will soon complete their strategic reviews, while other central banks are working on adding new instruments to their toolkit.

Still behind the curve – Fed, BoE, and ECB

This year, the US will see 7% growth and 4% inflation. Global growth will hover around 6%, and even European inflation may reach 2%. Still, the Fed has leaned against all strong data points since March and is pointing to some hikes in 2023. Strong inflation prints continue to be deemed temporary, despite signs of non-transitory factors. The BoE has so far also shrugged off inflation pressures from reopening and input prices raised by currency depreciation and Brexit costs. The ECB is likely to remain dovish, adding a symmetric inflation target of 2% at the end of their strategic review.

The hawks – alive and kicking

At the global level, some hawkish turn has taken place, just outside the US and Europe, so that for once, monetary tightening leaders are outside the US. In China, the PBOC has maintained a very cautious approach throughout the pandemic, with no QE introduction and positive real rates across the curve. Central banks in Brazil, Russia and Mexico countered April and May inflation with hikes. In Europe, Hungary and Czech Republic are tightening ahead of the ECB. Outside emerging markets, hawks are rarer, but Canada, Norway, New Zealand all pointed to tightening more proactively than the Fed. A flurry of hawks ahead of the Fed is uncommon, as both China and small open economies tend to follow the US in monetary cycles. We see this as a sign of the urgency brought about by inflation data. Larger central banks may follow smaller ones, for once.

Fed – next in line to turn hawkish

With dovish major central banks, but the number of hawks increasing, we think it is just a matter of time before the Fed gives in. US labour markets and inflation are showing signs of overheating, and both vaccine and macro momentum are ahead of Europe. The politics of hiking is also less complicated compared to the ECB. The global monetary policy summit at Jackson Hole (August 26-28) could be the opportunity for a hawkish turn. By then, both transitory components of inflation and labour market weakness will have subsided, and the vaccination campaign will be essentially complete. Clearer visibility on the economy and inflation forces will then make it easier for Powell to turn.

Monetary toolkit – big changes are on the way

The monetary toolkit saw only small changes in 2020. The stimulus has been unprecedented but took place mostly through a strong reliance on existing tools, rate cuts and QE. In August, the Fed increased the weight of its focus on employment, as well as allowing for average inflation-targeting. The changes made the reaction function slightly more dovish – however, the Fed remained vague on how long they would let the economy run hot, until recently. The ECB will conclude its strategic review this summer. Besides the shift to a symmetric target, housing costs might be included. A few countries introduced yield curve control (notably Australia), but the policy failed to be broadly adopted. Over time, new monetary tools may be needed – central banks are already working on these, as shown below.

CBDC – a pathway to helicopter money?

The next 12-24 months will be focused on discussions of monetary tightening. Still, the pandemic brought about more work on additional monetary options. The next downturn will see a richer monetary tool available to central banks. One key idea will be Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). With CBDC, the public directly accesses central bank money, without passing through commercial banks. Depending on the architecture, central banks may have full information and oversight on every transaction and can therefore implement tiered interest rates specific to every economic sector or region. The PBOC has implemented the digital yuan with exactly this in mind. More than 85% of the world’s central banks are working on CBDCs already, and the ECB plans to launch a digital Euro by 2025.

Conclusions: Carry trades’ last dance

Investors are heavily betting on carry trades, supported by a consistent dovish message from central banks.

We believe one-sided market positioning and fragility, rather than extreme inflation, are the reasons why investors should tread cautiously. Several events have already raised red flags on systemic risk this year – GME, RobinHood, Archegos. With accelerating macro data and plentiful liquidity, the contagion was minimal. However, these macro and liquidity tailwinds are likely to become headwinds over the coming months. We see limited value in credit, where most indices are at record tights. We are selective in our approach to credit investing, maintaining exposure to transport, energy, industrials and consumer firms linked to economic reopening. We see more value in cash bonds than CDS spreads, where data shows all-time-long risk positioning. We also find value in convertibles, which sit outside of central banks’ eligible universe and often offer attractive upside/downside convexity. We are starting to see value in emerging markets hard currency debt as well as local currency, in countries where current accounts are boosted by commodity prices and central banks are ahead of the curve – like Brazil and Russia.

Ultimately, central banks might not be able to fully normalise policy – but they will try. The future policy path will depend on politics and political constraints. A Google Ngram search shows inequality is a more popular word than earnings or revenues, for the first time in centuries. The political pendulum is shifting towards more investment, redistribution and more taxes. The political constraint that comes with this is a higher stock of government debt. In the long run, this means real rates will likely remain below inflation.

For more information about Algebris and its products, or to be added to our distribution lists, please contact Investor Relations at algebrisIR@algebris.com. Visit Algebris Insights for past commentaries.

This document is issued by Algebris Investments. It is for private circulation only. The information contained in this document is strictly confidential and is only for the use of the person to whom it is sent. The information contained herein may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose without the prior written consent of Algebris Investments.

The information and opinions contained in this document are for background purposes only, do not purport to be full or complete and do not constitute investment advice. Algebris Investments is not hereby arranging or agreeing to arrange any transaction in any investment whatsoever or otherwise undertaking any activity requiring authorisation under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. This document does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of an offer to subscribe or purchase, any investment nor shall it or the fact of its distribution form the basis of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract therefore.

No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information and opinions contained in this document or their accuracy or completeness. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document by any of Algebris Investments, its members, employees or affiliates and no liability is accepted by such persons for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

This document is being communicated by Algebris Investments only to persons to whom it may lawfully be issued under The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 including persons who are authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 of the United Kingdom (the “Act”), certain persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, high net worth companies, high net worth unincorporated associations and partnerships, trustees of high value trusts and persons who qualify as certified sophisticated investors. This document is exempt from the prohibition in Section 21 of the Act on the communication by persons not authorised under the Act of invitations or inducements to engage in investment activity on the ground that it is being issued only to such types of person. This is a marketing document.

The distribution of this document may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. The above information is for general guidance only, and it is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this document to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. This document is suitable for professional investors only. Algebris Group comprises Algebris (UK) Limited, Algebris Investments (Ireland) Limited, Algebris Investments (US) Inc. Algebris Investments (Asia) Limited, Algebris Investments K.K. and other non-regulated companies such as special purposes vehicles, general partner entities and holding companies.

© Algebris Investments. Algebris Investments is the trading name for the Algebris Group.